As interim President Ahmad al-Shara’a travels to New York to attend the UN General Assembly, he departs an increasingly fractured country. In power since Bashar al-Assad fled to Moscow last December, al-Shara’a has positioned himself as the leader of Syria’s political transition after more than 14 years of war and decades of rule under the Assad family. So far, his scorecard is mixed: al-Shara’a and his team, comprised largely of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) insiders and affiliates, may have steered the country away from all-out collapse, but patterns of authoritarianism are emerging. Nowhere is this more obvious than the gulf between interim authorities’ international and domestic diplomacy.

Faltering public opinion

Under al-Shara’a, Syria has reemerged from its isolated pariah status under Bashar al-Assad. Damascus has hosted high-ranking foreign officials, while al-Shara’a himself has travelled to 16 countries for official visits, meeting crucial regional players (Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Egypt, Qatar) and western states (France, US). After years of stalled talks with the former regime, al-Shara’a represents a break after years of stagnant diplomacy. Regional and international leaders are right to seize the opportunity to engage with Syria’s diplomats but should be wary of doing so at the expense of real progress for Syrians themselves.

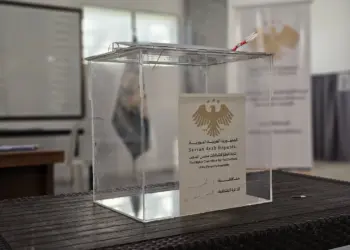

With the country still fractured, the economy hitting recovery roadblocks, and sectarian tensions ongoing, it’s clear that al-Shara’a and the interim authorities are more popular abroad than at home. Between May and June 2025, ETANA conducted surveys to measure the public opinion on Syria’s transition so far. The results, compiled before the violence in Suwayda in July, revealed a polarized public: as many as 85% of Sunni respondents reported feeling safe in Syria, compared to just 21% of Alawites and 18% of Druze. Overall, 77% of minority respondents said that Damascus did not represent their interests.

Performative governance

In the immediate aftermath of the March coastal massacres, interim authorities announced a handful of highly publicised arrests and established a national fact-finding committee. Yet months later, the committee’s full findings—especially details about chain of command, responsibility, and methodology—have not been released to the public, fuelling distrust among victims’ families and Alawi communities. A UN Commission of Inquiry report already found that violence was widespread, sectarian in character and likely amounted to war crimes, calling for independent investigations, prosecutions and better vetting of security forces. To date, however, there have been no known prosecutions of senior figures and formal reparations have not been implemented at scale. Many therefore view the government’s responses as largely tokenistic.

Most recently, Damascus, Washington, and Amman announced a tripartite “roadmap” for Suwayda following the clashes and large-scale killings that took place in July. The roadmap was touted as a major step in post-conflict reconciliation—but failed to include buy-in from Suwayda’s leaders. The marginalization of local figures and absence of justice for Suwayda’s victims is stoking fears among Syria’s minority communities, especially as eyes turn toward the Kurds in the north-east.

With nominal support from western and regional leaders, Syria’s interim authorities simply do not have to prioritize domestic legitimacy. The sentiment seems to be that if they can appease Istanbul, Doha, Washington and Paris then they do not need to appeal to Syrians themselves, in all their diversity. This is a mistake: long-term stability for Syria relies on buy-in from all of the country’s communities, many of whom are understandably wary of a return to the highly centralized and authoritarian governance that defined life under the Assads.

Damascus should genuinely pursue justice and accountability in the wake of violence, which, in some cases, means holding its own people responsible. Getting buy-in from Syria’s many communities will be a hard task, but fears of authoritarianism may be abated if Damascus genuinely opens the door for inclusive governance and representation. The Syria crisis is not an easy fix, but pursuing a Syrian-centred approach will create more lasting peace and stability. If al-Shara’a prioritizes his standing abroad rather than at home, he risks losing Syria’s fragile peace.