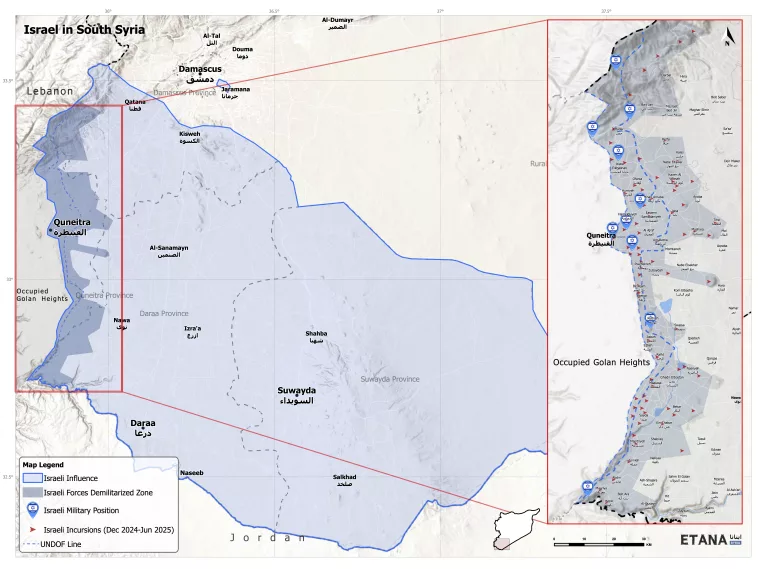

On the same day that Syrians took to the streets to celebrate the downfall of Bashar al-Assad, Israeli forces entered Syrian territory for the first time in decades—supposedly a temporary measure amid the jubilance, uncertainty and insecurity of the immediate post-Assad moment. However, there have been few signs of temporariness since then. After occupying hundreds of square kilometers of territory beyond the occupied Golan Heights, Israel has effectively created four zones inside Syria that allow it to deploy troops in forward positions outside Israel or Israeli-occupied territory, to conduct regular raids inside Syria, or to project Israeli influence deep within Syria through aerial surveillance and airstrikes.

Israel’s actions in Syria from 8th December 2024 have repeatedly violated Syrian sovereignty and deeply destabilized the already-fragile transition taking place in the country. At the same time, steps taken by the interim administration itself—including power consolidation by hardline Islamists and the integration of ISIS-linked figures into the security forces—have only enabled a more aggressive Israel that has demonstrated it will, particularly in the wake of 7th October, secure its borders at any cost. Although there are few signs to date of significant military threat facing Israel from Syrian territory, Israel’s occupation and entrenchment across south Syria is only expected to intensify, even if the result is fueling conflict dynamics and violence within Syria.

Recent Israeli actions in Syria indicate a desire to keep interim authorities within Israeli-defined red lines; recent strikes on the Ministry of Defense and other sites in Damascus in response to violence in Suwayda were a strong warning from Israel that it could exact significant costs if interim authorities do not play by the rules set by Tel Aviv. However, recent Israeli airstrikes in Suwayda and Damascus hardened interim authorities’ position against Druze factions in the south and have made concrete the sectarian divisions and mutual suspicion between the two warring sides—another example of how Israel’s hand in the south is both destabilizing and harmful to an already-fragile post-Assad transition.

Background

Under Bashar al-Assad, Syria played a vital role as a territorial, logistical and ideological conduit in service of Iran’s strategic objectives in the region. The regime utilized Syrian territory, military-scientific infrastructure and the army and security apparatus to produce advanced weaponry in service of Iran’s regional objectives and arsenal of drones, ballistic missiles and other arms, with many of these weapons bound for Hezbollah in Lebanon. At the same time, however, Israel maintained a sort of familiarity with Assad despite Iranian entrenchment: he was a known entity they could contain vis-à-vis Israel itself. Russia had also acted effectively as a guarantor between Syria and Israel over the decades long rule of the Assads. Under this arrangement, Israel could lean on Russian officials to raise concerns and/or reassert red lines—an understanding that resulted in the Israeli-Russian deconfliction mechanism for south Syria upon Russia’s intervention in the Syrian conflict in 2015.

The contours of these formal and informal agreements changed irrevocably in the wake of Israel’s regional escalation following Hamas’ 7th October 2023 attacks in Gaza and Israel. In Syria, this was characterized by ground incursions, the establishment of defensive fortifications inside Quneitra proper, and a unilateral campaign of airstrikes that resulted in the deaths of top Iranian and Hezbollah commanders and command-control infrastructure. Iranian proxies’ repeated use of Syrian territory to stage cross-border rocket and drone attacks targeting the Israeli-occupied Golan Heights and Israel proper also created new rules of engagement with the regime, with Israel hitting regime units and bases seen to be collaborating with, or tacitly facilitating, Iranian and Hezbollah activity on Syrian soil.

However, the collapse of the regime, and the ascent of Salafi-jihadi and former Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) leader Ahmad al-Shara’a to the interim presidency, presented Israel with an all-new strategic dilemma: an unpalatable and unfamiliar government on its border. Israel’s reaction was swift: immediately after the regime’s fall, Israeli Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu signaled that Israel would no longer recognize the 1974 demilitarization agreement related to the Israeli-occupied Golan and the demilitarized UN Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) border strip in Quneitra province. Speaking from the occupied Golan on the same day that Syrians were taking to the streets to celebrate the removal of Assad, Netanyahu announced that he had ordered Israeli forces to “take over positions [abandoned by the regime’s army] to ensure that no hostile force embeds itself right next to the border of Israel,” a situation he claimed would be temporary “until a suitable arrangement is found.” No matter how ambitious, these were only initial steps. In effect, Israeli forces occupied the entirety of the 235-square-kilometer border strip while the Israeli Air Force launched one of the largest aerial campaigns in history to destroy regime weapons stocks and significantly degrade the capabilities of what remained of the Syrian army.

Although these were interventions initially predicated on a narrative of national security, Israel has used direct and implicit threats of further attacks to effectively demilitarize almost all territory south of Damascus and define the security make-up and nature of Syria’s post-Assad transition. In the six months since the collapse of the regime, Israel has built up its military occupation of the border strip, attacked military units in Quneitra and Daraa, and projected Israeli influence deep into the country through a combination of ground incursions, penetrative, disruptive airstrikes and on-the-ground soft power efforts. Airstrikes targeting Ministry of Defense units and allied armed groups attacking Druze formations in and around Damascus earlier this year, and then again in Suwayda in July, also set another red line around Suwayda and the rest of the country’s Druze communities, presenting interim authorities with another intractable problem to its ambitions across the country.

One constant since Israel’s founding in 1948 is that once it has taken control of territory, it almost never relinquishes it (its withdrawal from south Lebanon in 2000 only resulted from a concerted, highly effective guerilla campaign by Hezbollah). Instead, Israel creates new realities on the ground and then exacts concessions from regional states.

Israel’s strategic objectives in south-west Syria

Ultimately, Israel’s occupation of, and interventions in, south-west Syria are guided by four over-arching strategic objectives:

- Security: Israel’s occupation and penetration of further Syrian territory (beyond the occupied Golan) has given it control of strategic high-points in the region that allow it greater reconnaissance and intelligence reach into both Syria and Lebanon.

- Control of the Hermon Range: Similarly, control of the Hermon Range mountain range provides effective surveillance coverage over the entire region of south-east Lebanon.

- Water security: After its post-Assad intervention in Syria, Israel now has direct control of, or indirect access to, most of the areas rich in surface water resources in Quneitra and western Daraa. Israel’s area of operation currently includes the main valley courses in Quneitra, in addition to over a dozen dams in Quneitra and Daraa.

- Soft power: Israel views community outreach in the south as a way to complement its security control over the region but also to facilitate normalization from the ground-up. Much of these efforts have so far focused on Quneitra, which has largely been demilitarized in the past few months.

Four zones of operation

While the border strip in Quneitra and southern governorates can be viewed as a concentrated area of Israeli presence, regions across Syria have become part of an active operational theater that helps define Israeli strategic interests around the country. In effect, Israel’s on-the-ground presence and wider involvement in Syria since the fall of Assad can be delineated into four zones, each with their own specific military and security conditions and motivations:

- Active deployment zone;

- Incursions zone;

- Aerial security zone;

- Strategic influence zone.

Active deployment zone

Israel’s zone of active deployment largely follows the borders of the former demilitarized border strip in Quneitra, ranging from the Syrian-Lebanese border in the north and down to the Yarmouk Basin in the south. As a foothold within Syria proper (as opposed to occupied Syrian territory in the Golan Heights), this zone essentially serves as a forward position for launching incursions and larger-scale military operations.

To secure this area, Israeli forces have carried out comprehensive combing and disarmament operations in cities, towns and villages up and down the border strip. Israeli forces are expected to expand this zone to incorporate (occupy) all of Quneitra province (and parts of Rural Damascus and western Daraa) in the coming period—another gross breach of Syrian sovereignty and international law.

Soft power & community outreach

The Israeli deployment zone is considered a relatively safe area for troop movements and a suitable environment for soft power interventions aimed at building relations between Israeli forces and local populations in the south. In recent months, one key fulcrum of Israel’s presence in the area has been community outreach.

As part of these outreach efforts, Israeli forces delivered five shipments of relief baskets (consisting of food and medical supplies) to Abu Tineh, Al-‘Asha, Bureiqah, Al-Rafid and Saida al-Jolan between 10th March and 12th May. In total, though, ETANA documentation recorded 10 aid delivery operations by Israeli forces since late last year. Initially, Israeli relief efforts were met with resistance from local communities, with several reports at the time of community members refusing or destroying relief baskets. Later, however, the local population became more interactive with relief aid provided by Israel. This can be explained by Quneitra’s historical economic disadvantage under the Assads as well as post-Assad economic instability.

Incursions zone

According to ETANA documentation of Israeli activities since the fall of Assad, Israeli forces conducted at least 130 ground incursions since late last year, however when counted alongside other types of operations—such as road closures (76), destruction of military equipment (13), establishment of military positions (12) and arrest campaigns (11)—the total number of ground-based Israeli transgressions on Syrian territory is well over 200.

The area of Israel’s zone of incursions covers approximately 600 km2 of territory. Further north, the incursion zone also covers Druze villages adjacent to the Syrian-Lebanese border in Rural Damascus province. In effect, this zone incorporates much of the Yarmouk Basin in south-west Daraa, what remains of Syrian-controlled Quneitra province, and dozens of square-kilometers of territory in south-west Rural Damascus.

One conclusion drawn from this initial mapping is that Israel has targeted all of the main water resources feeding the Jordan River, from the village of Al-Qusayr which sits just above the Al-Wahda Dam on the Syrian-Jordanian border to the various lakes and reservoirs dotted across western Daraa and central Quneitra. In step with this strategic objective, Israel has targeted all military positions within the incursions zone. To cement this status quo, Israeli units have carried out dozens of raids and sweeps in border villages with the aim of disarming the local population and arresting potential or past members of groups accused of being affiliated with Lebanese Hezbollah in the south. So far, Israel has disarmed the population in the deployment area, prohibiting livestock grazing and almost completely banning any approach to the Israeli border.

Zone of aerial influence

Previous Israeli operations to target Iranian, Hezbollah and regime assets in Syria before December 2024 and to destroy all Syrian army units, camps and positions after December 2024, indicate that Israel’s zone of aerial influence actually covers the entirety of Syria. Airstrikes after the fall of the regime have targeted military sites from Latakia and Tartous on the coast to Aleppo, Damascus, Daraa and almost every part of the country. However, in relation to south Syria specifically, Israel’s zone of aerial influence extends as far as Damascus and eastern Suwayda. Significantly this zone covers the entire Syrian-Lebanese border strip as well, meaning it serves two purposes: to enforce Israel’s demilitarization of all territory south of Damascus, and to prevent the smuggling of weapons from Syria to Lebanese Hezbollah.

Israel began imposing intensive air surveillance over south Syria after mid-March 2025 using drones, following Tel Aviv’s intensive campaigns to destroy all Syrian army units, camps and positions in the immediate wake of the regime’s collapse. Netanyahu and Israeli Defense Minister Israel Katz issued explicit warnings to the new Syrian administration against the formation or deployment of units of the new army (affiliated with the interim Ministry of Defense) in these governorates.

Israel has repeatedly followed through on its threats to enforce a demilitarization of the south that is palatable to Israeli officials and military commanders in Tel Aviv. Beginning 11th March, Israeli air forces carried out more than 40 airstrikes targeting heavy equipment belonging to the Ministry of Defense, as well as sites and offices newly equipped by the Ministry of Defense, following interim authorities’ formation of a new, reformed 40th Division under the banner of the “Southern Division.” Despite this, the new administration attempted to test the seriousness of Israel’s warnings once again by opening a training camp for Southern Division members. It didn’t work: On 17th March, Israeli jets carried out more than 20 airstrikes targeting Southern Division sites, resulting in two deaths and 20 injuries.

Zone of strategic influence

While past Israeli actions in south Syria were, to a point, shaped by negotiation—not least the Israeli-Russian deconfliction mechanism negotiated after Russia’s intervention in Syria began in September 2015—almost all Israeli actions since the fall of the regime have been conducted unilaterally. Israel has therefore drawn the boundaries of its new strategic influence with fire, as was demonstrated in April when Israeli jets bombed the two most important airbases in central Syria to thwart a Turkish project to establish Turkish-backed air bases and install advanced air defense platforms in this area. Accordingly, the area of strategic influence amounts to approximately 53,000 km2 and includes the southern provinces of Damascus and southern Rural Damascus, Daraa, Quneitra and Suwayda as well as the southern half of Homs province.

Status quo following the Israel-Iran war

Syria’s ongoing vulnerabilities were only compounded when, in mid-June, Israel launched a wave of aerial attacks targeting Iranian nuclear facilities, military and Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) commanders and scientists, and other key infrastructure across Iran. Syria found itself quite literally in the middle of the hostilities. Iran retaliated with several barrages of high-speed ballistic missiles and drones. Both sides repeatedly utilized south Syrian airspace to conduct cross-regional attacks, with interim authorities effectively powerless to intervene and keen to limit the threat of spillover hostilities.

For the moment, tensions between Tel Aviv and Tehran have quieted, but Syria remains at risk so long as Israel perceives Syria’s instability as a national security threat to itself. That includes the risk of regime remnant groups operating with a small footprint in south-west Syria. These groups do not pose a significant threat but could further destabilize already-fragile security dynamics by launching scattered, small-scale rocket attacks towards the Golan. Incidents like this would further undermine the little trust that exists between Israel and the new Damascus government and potentially recreate in the south-west the kind of Israeli rules of engagement that existed when Assad was still in power: Israel punishing authorities in Damascus for failing to stop cross-border attacks from the south-west.

While Israeli forces maintain a fixed military presence in the Quneitra border strip, this area was expanded amid Iran-Israel hostilities to include towns in western Rural Damascus while also extending along the Damascus-Quneitra highway. This expanded area is significant because of its proximity to Damascus—Beit Jinn is just 35km from the outskirts of the capital—as well as its mixed sectarian make-up, with several Christian and Druze villages nestled in the foothills of the Hermon Range between the Syrian-Lebanese border and south-west Damascus. As such, Israel’s operational area of incursions now effectively includes all of Quneitra province and the Yarmouk Basin in south-west Daraa.

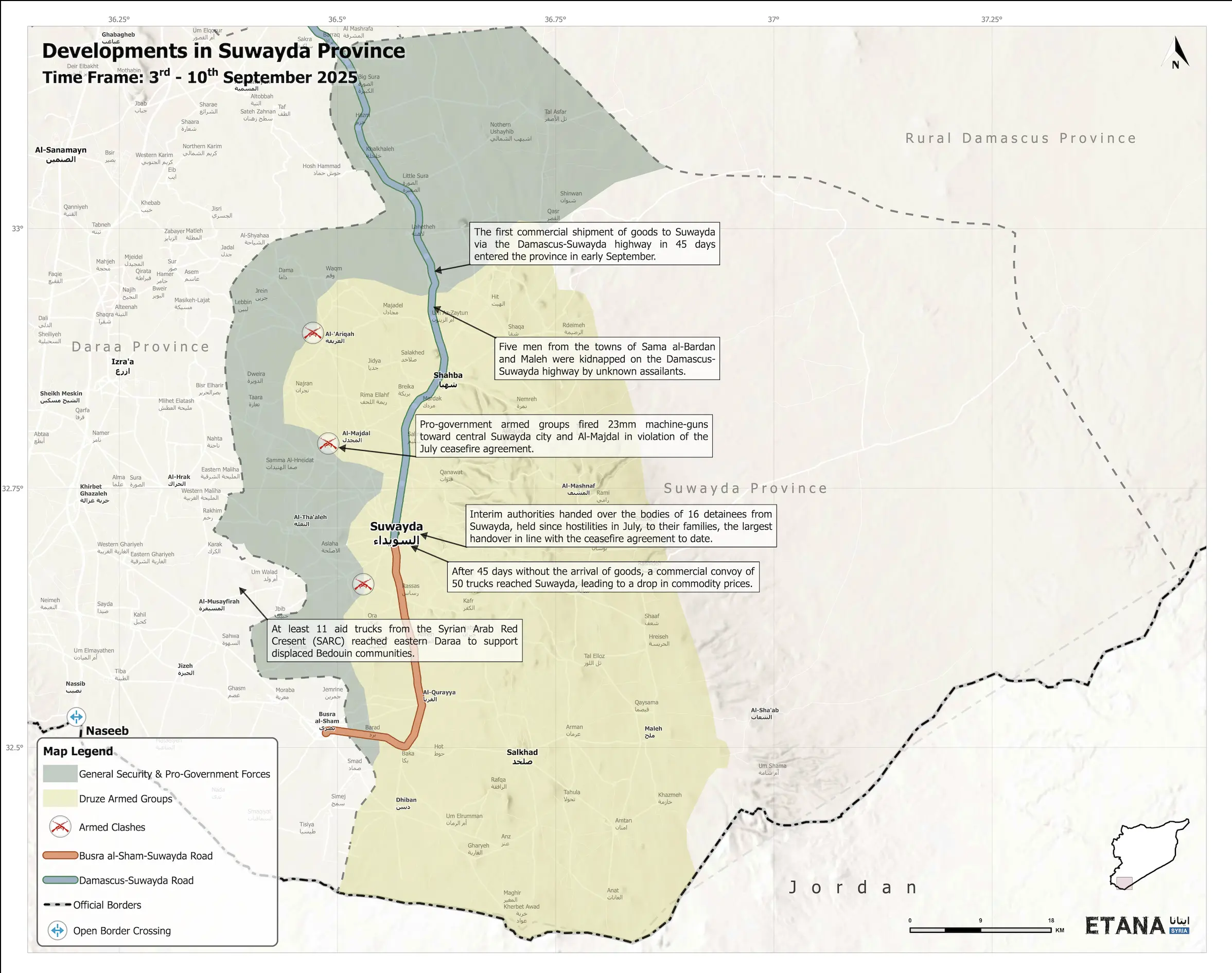

Status quo following escalation in Suwayda

Since taking and beginning to consolidate power in the wake of the Assad regime’s collapse, interim President al-Shara’a aimed to disarm Druze factions in Suwayda and integrate them into the interim Ministry of Defense—the same objective that was applied to the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in north-east Syria, Ahmad al-Awdeh’s groups in eastern Daraa, and other unaffiliated armed actors across the country, albeit with differing degrees of negotiation and force. However, Suwayda has proven to be a more intractable problem for al-Shara’a and interim authorities, not least because of Israel’s intervention and self-proclaimed “protection” of the Druze minority in Syria. The purpose of this stated aim is twofold: to domestically message to Israel’s own influential Druze minority an image of Israel as a protector of the Druze and to enforce protection of Israel’s undeclared national borders and its national security vis-à-vis the region.

Israel’s role in Jaramana & Ashrafiyat Sahnaya violence, April-May 2025

Interim authorities initially tested Israel’s mettle during the clashes in April in Jaramana and Ashrafiyat Sahnaya. On 27th April, an audio recording allegedly depicting a Druze cleric insulting the Prophet Muhammad was leaked online, sparking widespread anger and calls for retribution from some Sunni segments of the population. Violent protests against the recording and targeting Druze students initially broke out on university campuses before spreading to up to 70 locations across the country. On 28th April, local armed groups and General Security units attacked two Druze areas around Damascus, Jaramana and Ashrafiyat Sahnaya, with dozens killed on either side in the subsequent clashes.

It was at this point that Israel established another red line beyond the demilitarization of the south. A joint statement from Netanyahu and Defense Minister Israel Katz vowed to stop attacks against Druze groups or communities, as well as Suwayda itself: the two officials claimed subsequent Israeli strikes in Sahnaya were a “serious message” that “Israel expects it to act to prevent harm to the Druze.” This further pitted interim authorities against the Druze, with al-Shara’a increasingly turning to language of the Druze as wayward members of Syrian society or, at worst, separatists working against the interests of the new, post-Assad state. And while Israel’s strikes in Ashrafiyat Sahnaya appeared to stave off interim authorities’ ambitions in Suwayda, this kind of highly sectarianized nationalistic discourse returned in July when interim authorities again attempted to move on the Druze-majority province.

Israel’s role in Suwayda-wide violence, July 2025

In comparison to the violence near Damascus, Israel’s response to recent pro-government attacks on Suwayda was less immediate. After clashes between Bedouin groups and Druze factions broke out mid-July, the interim Defense Ministry deployed more than 12,000 reinforcements to exact concessions from the Druze. After cautiously watching developments for 24 hours, Israel unleashed a wave of airstrikes against pro-government forces advancing into north and western Suwayda, reportedly killing as many as 300 fighters from the Ministry of Defense, General Security and affiliated armed groups. Subsequent airstrikes hit several sites in central Damascus, including the Ministry of Defense building, as well as the People’s Palace itself—both targets intended as strong warnings to al-Shara’a and the remaining interim authorities to stand down.

However, after a second-wave attack between 17th and 18th July, spearheaded by Bedouin militias backed by interim authorities, Israel began to show some flexibility—initially messaging that it would permit General Security units to enter Suwayda city for a limited period (part of an initial ceasefire agreement that did not hold) and then acquiescing to a tripartite ceasefire agreement on 20th July (brokered between Syria, Jordan and the US) that is still tenuously holding. This was likely the result of pressure from the US administration to quell fighting in the south rather than a stand-down by Israel from its previously stated position of “protecting” the Druze in Suwayda.

In many ways, the damage is already done. Although the tripartite ceasefire is mostly holding despite hotspots of fighting along key axes in northern Suwayda province, Syria’s discourse, between the central state and the Druze, is fragile, if not already broken. Looking forward, the language now being used almost guarantees further violence in the future, and this serves as another example of Israel’s expanding and destabilizing presence in south Syria. In the meantime, a tripartite meeting between Syrian, Jordanian and US officials on 12th August in Amman saw the formation of a working group to oversee the ceasefire. Even so, interim authorities appear to view the current ceasefire as a tactical one and, notwithstanding the near blockade imposed by authorities around Suwayda as of mid-August, more significant attacks against Suwayda will likely recommence once al-Shara’a figures out his next approach and the ceasefire has served its purpose in the short to medium term.

Assessment

Despite Israel’s initial claims that its presence in Syria after Assad would be “temporary,” evidence points to a growing unchallenged occupation and entrenchment of Israeli forces on Syrian territory. While Tel Aviv’s repeated, systematic aerial bombardments and ground incursions serve Israel’s stated objective to demilitarize areas of south Syria adjacent to the occupied Golan, together, its activities in the region are highly strategic, effectively giving it a defining—and destabilizing—hand in Syria’s post-Assad transition.