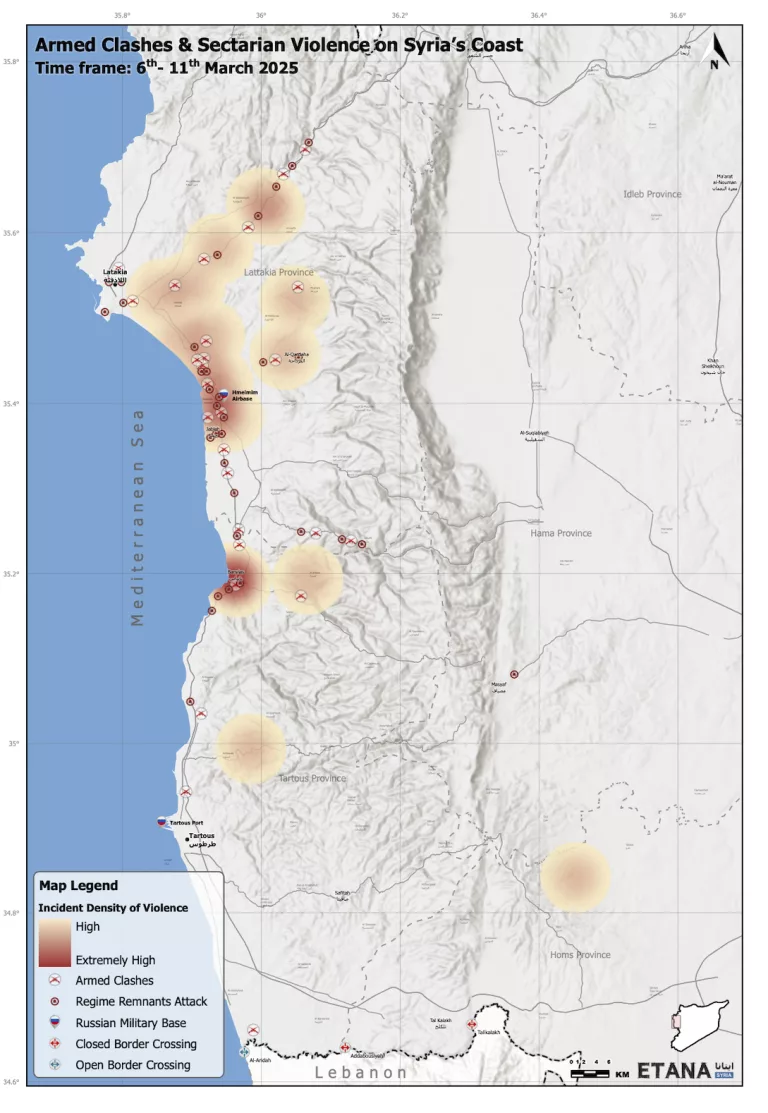

The worst bout of violence of Syria’s post-Assad period ended with more than 1,000 civilians estimated dead. What began as a series of coordinated ambushes by regime remnants in Jableh in southern Latakia quickly expanded into an insurgency across Latakia and Tartous, Syria’s coastal provinces. The attacks opened the door for armed groups affiliated with caretaker authorities to carry out revenge attacks and sectarian violence, predominantly targeting Alawi communities. Graphic videos and images circulated online depicting armed men executing, torturing and humiliating civilians.

The implications of the violence have been far-reaching, raising urgent questions about the current shortcomings and trajectories of the post-Assad transition so far. For one, they have done significant damage to caretaker authorities’ international standing, perhaps one of the reasons why caretaker President Ahmad al-Shara’a sealed an agreement with the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) in the days afterward. The failure of caretaker authorities to integrate various factions affiliated with caretaker authorities under a cogent, professionalized Ministry of Defense undermines its ability to respond appropriately to security situations in the country—as demonstrated by the myriad violations committed in Latakia and Tartous, with many of these armed groups operating semi-independently within the new security forces. Despite some initial steps towards accountability—including the formation of a fact-finding committee tasked with investigating the events of early March—violations continued after the official declared end of military operations on the coast; Syrian communities on the coast and in other parts of the country are now watching developments around the country anxiously.

Outbreak of Violence in Latakia

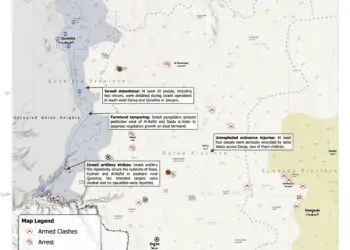

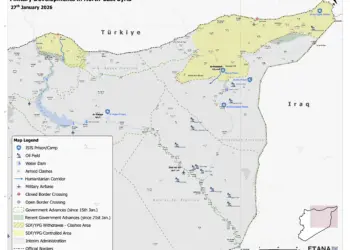

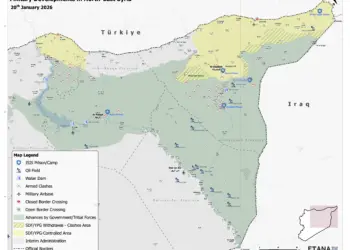

Regime remnants ambushed General Security troops in a series of coordinated attacks near the town of Jableh in rural Latakia, killing at least 15 members of security forces on 6th March. After the initial regime remnant ambushes that killed 15 General Security members in Jableh on 6th March, ambushes and surprise attacks were reported in Latakia, Jableh, Baniyas, Tartous and surrounding villages but were most intense in the mountains around Qardaha, the ancestral village of the Assad family. Pro-regime insurgents operating under the so-called “Military Council for the Liberation of Syria” were led by Ghiath Dalla, the former commander of the 42nd Brigade of the 4th Tanks Division and the Al-Ghiath Forces alongside former regime officers inside the Hmeimim base near Jableh. Other prominent regime figures reportedly involved include: Liwa’ Dara’ al-Sahel (Coastal Shield Brigade) commander Miqdad Fteiha, Quwaat Suqour al-Sahra (Desert Hawks) commander Muhmmad Mehrez Jaber, and groups linked to Tiger Forces commander Suheil al-Hassan.

Regime remnants executed multiple security force troops and burned their bodies while also attacking civilians including paramedics, journalists and motorists travelling on local roadways. As caretaker authorities mobilized more forces from other areas of the country, regime remnants withdrew to Hmeimim and the mountains around Qardaha. Syria’s caretaker minister of defense immediately ordered a general mobilization of forces to head to the coast to “control the general situation and protect civilians and state institutions.”

The Military Operations Administration subsequently claimed that as many as half a million fighters mobilized against what it called the “Nusayri coup”—using a derogatory term for Alawis often used by hardline Islamist groups including ISIS. However, ETANA estimates that approximately 70,000 Military Operations Administration, General Security, Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS), Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) and unofficial fighters deployed to the coast—still a huge number—that reflected a significant popular groundswell of support for caretaker authorities to oppose the regime insurgent threat. Tanks, armored vehicles and helicopters were also mobilized as part of this push. Regime remnants were gradually pushed out of urban areas—sometimes destroying and setting fire to civilian infrastructure during their retreat—with security forces using helicopters, drones and artillery to target regime positions in outlying mountainous areas.

Sectarian Violence

After deploying to the coast, armed groups moved neighborhood to neighborhood and village to village as part of “combing operations,” perpetrating extra-judicial killings, field executions and massacres—sometimes after explicitly asking Alawi residents to identify themselves. Sunni civilians from these communities were also killed in the violence, although in far fewer numbers. Killings and massacres were reported in at least 20 villages, neighborhoods and areas, including: Ain al-Arous, Astamou, Bayt Alia, Birabshou, Bustan al-Basha, Jableh, Al-Mukhtariyeh, Al-Qabou, Al-Qardaha, Al-Rameileh (Jableh), Al-Shayr, Al-Shilfatiyeh, Al-Snouber and Al-Zoubar in Latakia province; Bustadah, Dahyet Bouqah, Al-Da’tour, Al-Da’tour Bustadah and Al-Muntazah in central Latakia; Baniyas and Hay al-Qusour in Tartous province; and rural Masyaf in Hama province.

ETANA reviewed dozens of videos and images from the incidents, the majority of which depicted acts of violence and forced humiliation targeting unarmed civilians. In several, armed gunmen used explicitly anti-Alawi slurs; in others, groups of unarmed civilians were made to crawl on the ground at gunpoint.

Despite initial claims that HTS-aligned foreign fighters were primarily responsible for the sectarian violence that followed, open-source analysis by ETANA and other Syrian and human rights organizations points to the notable involvement of official security forces as well as two Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA) factions: the Suleiman Shah Brigade (led by notorious militia figure Abu Amsha) and the Al-Hamza Division, both of which have been accused of involvement in myriad human rights abuses against Kurdish and other civilians in north-west and north-east Syria.

Aside from the more targeted violence on the ground, a video emerged of unknown security forces indiscriminately dropping makeshift barrel bomb munitions from a helicopter over the coast. Geo-location analysis by ETANA indicates this was done over the region of Bustan al-Basha, between Latakia city and Hmeimim. The fact these forces were in a helicopter requisitioned from regime forces in December suggests the individuals responsible are from official security forces under the Military Operations Administration.

Misinformation, some of which was repeated by international political figures, also ran rampant as videos began to circulate online. On one side, pro-caretaker government channels down-played the scale of the violence. On the other, false narratives rapidly spread exaggerating the targeting of Christian communities, although seven Christian civilians were reported to have been killed in the violence.

Obituaries posted to Facebook quickly indicated that hundreds of civilians were killed. The Syrian Network for Human Rights (SNHR) is reporting that at least 1,084 people died as a result of extra-judicial killings in Hama, Latakia and Tartous provinces between 6th and 17th March, although there are expectations that the total casualty toll could increase further in the coming days. According to SNHR, violations included “extrajudicial killings, field executions, and systematic mass killings motivated by revenge and sectarianism.”

Hostilities, sectarian massacres and fears of further violence pushed thousands of Syrians to seek refuge across the border in Lebanon, with many crossing the Al-Kabir River into northern Lebanon’s Akkar Governorate. While Lebanese authorities initially announced that approximately 6,000 Syrians and 40 Lebanese families had entered Lebanon, UNHCR stated that at least 15,000 new arrivals had crossed to Lebanon as of 17th March.

Snapshot: Birabshou village massacre

Three days after the Jableh attacks—on 9th March—the violence reached Birabshou, a northern Latakia village less than 15km inland from the provincial capital. That day, a Latakia-based journalist posted on Facebook after hearing about violence in the village. The following day, photos and videos of the dead began to emerge online, many of them graphic and showing evidence of brutal killings. A widely-circulated video from Birabshou shows dozens of covered bodies on the side of a road, surrounded by mourners. Off-camera, a woman alleges that General Security forces used tractors to move the bodies. (A tractor can be seen in the background of the video.) As with other areas in the coast, the perpetrators set fire to cars and property upon their retreat.

ETANA reviewed social media posts listing the village’s dead, with casualty counts ranging from around 30 to more than 57 individuals. In many cases, victims were members of the same family. Based on Facebook posts from surviving family members, at least seven members of the same family were killed. Among them was a professor based in Iraq, who was in Latakia visiting family for spring vacation.

Aftermath: Arrests & Accountability

Responding to the outrage against the violence, security forces conducted a handful of arrests of fighters allegedly responsible for violations against civilians on the coast, believed to be from the Military Operations Administration and General Security. Although ETANA could not independently verify the total number of these arrests, the fact they were filmed indicates caretaker authorities’ desire to project an image of accountability. ETANA could also not confirm whether or not those arrested were responsible for the violence on the coast and, if so, in what capacity. Even so, the violence has validated longstanding fears among Alawis and other minority communities about retributive attacks after the fall of Assad.

Investigation & peace committees

Caretaker President Ahmad al-Shara’a’s first speech after the outbreak of violence on the coast was bellicose and aggressive, calling for the “liquidation” and “purification” of regime remnants. Once the extent of the sectarian violence became clear, al-Shara’a delivered a second, more conciliatory speech and formed two new bodies: an independent national fact-finding committee to investigate the events of 6th March and a supreme committee to communicate with coastal communities and “strengthen national unity during this sensitive period.” As with past governance steps taken by caretaker authorities, the selection process behind these committees was opaque, with questions remaining about the qualifications, representativeness and neutrality of many of their members.

The Committee to Investigate Events on the Coast consists of five judges, one defected Criminal Security Branch officer and one lawyer: judges Juma’a al-Dubais al-Anzi, Khaled Adwan al-Helou, Ali al-Nu’man, Alaa’ddine Latif, Hanadi Abu Arab; defected Criminal Security Branch officer General Awad Ahmad al-Ali; and lawyer Yasser al-Farhan. It will investigate events on and after 6th March and is due to submit its findings to the presidency 30 days from its formation. There is no clear Alawi representation on the committee, although there is speculation that Latif and al-Nu’man both hail from coastal provinces.

The Supreme Committee for Civil Peace, meanwhile, has been tasked with communicating directly with coastal communities, providing them with support to protect their security and stability and to strengthen national unity. It consists of former Ahrar al-Sham leader Hassan Soufan (who comes from a prominent Sunni Latakia family); former Assad adviser Khaled al-Ahmad (who is Alawi); and former sheikh and opposition/HTS-affiliated figure Anas Airout (who comes from Baniyas). While the inclusion of al-Ahmad has been somewhat controversial online and in some opposition circles, he is the only Alawi representative on a committee otherwise comprised of HTS-affiliated figures from the coast.

Other Developments

At the beginning of the week, al-Shara’a and SDF leader Mazloum Abdi signed a landmark agreement that included a ceasefire and plans to integrate the SDF into state institutions, including the Ministry of Defense, before the end of the year. While caretaker authorities ceded some important demands to Kurdish authorities in the north-east—including “constitutional rights” offered to Kurds including the right to teach and use the Kurdish language—questions and uncertainties remain about the technicalities of integration and the extent to which the SDF and Kurdish-led political authorities can retain a palatable degree of decentralization vis-à-vis Damascus that has been hard-won after years of war and external threats.

Meanwhile, the violence on the coast seemingly confirmed some prominent Druze figures’ worst fears about the intentions and composition of caretaker authorities vis-à-vis Syria’s minorities. Although Druze representatives Laith al-Balous and Suleiman Abdelbaqi brokered a tactical services/security-oriented agreement with Damascus this week focused on issues such as policing, salaries and reform of state institutions, Sheikh Hikmat al-Hijri and the majority of political and armed groups in the province remain opposed to a comprehensive political agreement with caretaker authorities. As such, events on the coast have created another obstacle to already-floundering talks between caretaker authorities and Suwayda’s leadership, with an agreement not currently expected in the foreseeable future.