The collapse of the Assad regime in Syria has precipitated the end of the industrial-scale narcotics trafficking operation run by the regime’s security apparatus and Hezbollah. The impact on smuggling groups active in south Syria is pronounced, with a significant decline in cross-border smuggling attempts since December and trafficking reduced to a localized criminal enterprise. Despite hopes that the new authorities in Damascus will prioritize border security and crack down on illicit smuggling, for the moment there are too many other competing priorities in the post-Assad Syria and a fundamental lack of border security—despite the best efforts of local armed groups—without a unified army and trained border guards.

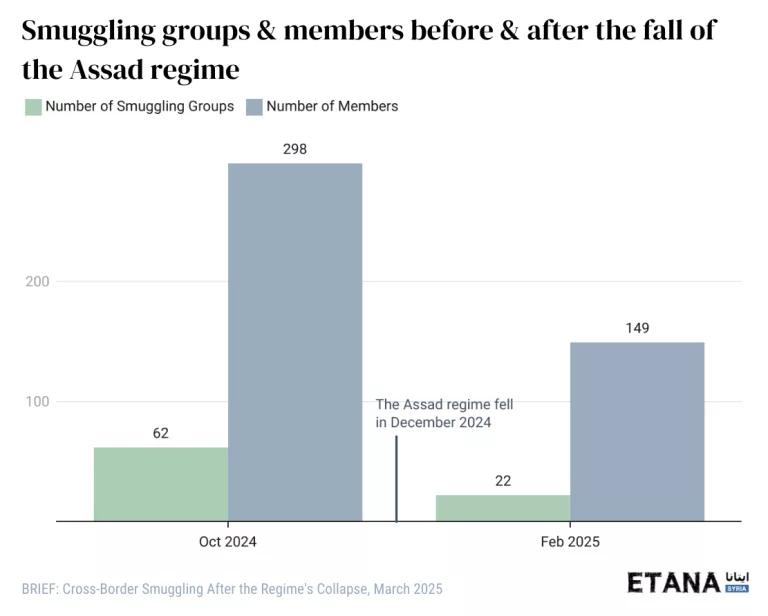

With the collapse of the Assad regime, there is now no organized umbrella to facilitate industrial-scale trafficking of drugs and weapons. The result is a massive decrease in cross-border operations by smuggling groups in south Syria: smuggling operations are infrequent, supply lines are less active, and smuggling groups are downsizing staff and equipment. ETANA assessed a downturn of almost 60% in cross-border smuggling attempts within the first two months of the regime’s fall, as compared to the same period in the previous smuggling season.

Meanwhile, many of the underlying causes that fueled the cross-border trade in the first place remain ever present in the border communities in south Syria. Without an improvement to the economic situation and better provision of security along the Syrian-Jordanian border, criminal elements will still seek to profit from this lucrative trade, even if they do not reach the economies of scale of the Assad regime’s narco-state. However, for now it is too early to judge whether it will be possible for smugglers to operate on anything near the massive scale seen between 2018 and 2024 under the Assad regime—although it seems unlikely—and whether the new authorities in Damascus can act as an effective regional partner to curb cross-border trafficking and maintain border stability.

Background: The Assad Regime’s Collapse and Its Effect on Cross-Border Smuggling

The Assad regime presided over a massive enterprise of drugs and weapons trafficking that spanned from Lebanon, Syria and onwards into Jordan and the Gulf. The collapse of the Assad regime in December 2024 laid bare for the first time physical evidence of the expansive smuggling infrastructure built and operated in close collaboration between the Assad family, the regime’s security apparatus and Lebanese Hezbollah, generating billions of dollars in illicit revenue for the regime through funneling immense quantities of weapons and narcotics into neighboring countries. The regime’s commitment to this criminal enterprise left a staggering effect on border communities in Syria and Jordan as criminal gangs operating in these areas with regime and Hezbollah oversight enriched themselves through cross-border smuggling and the proliferation of illicit drugs and arms in the region’s economically underprivileged towns and villages.

The fall of the Assad regime in December 2024 reduced south Syria’s smuggling networks to localized criminal groups as the industrial-scale operation run by the regime collapsed. With Assad and his inner circle gone, smugglers no longer had access to the strategic backing and security cover that allowed them to easily traverse central and southern Syria, while providing them with arms and equipment leading to a more militarized and sophisticated trafficking operation. At the same time, domestic production of Captagon largely ground to a halt, and the organized narcotics supply chain from Lebanon and Iraq facilitated by the regime and Hezbollah was degraded, although it did not stop completely.

In the absence of the regime’s support, significant numbers of smuggling groups in south Syria have totally disbanded while virtually all have thinned in number. Although cross-border smuggling has not completely ended, it has experienced a significant decline, with local smuggling groups dealing the pre-existing supply of drugs largely within Syria. ETANA estimates a decrease of 60% between smuggling attempts in the immediate aftermath of the regime’s collapse (between December 2024 and January 2025) compared with the same timeframe during the previous smuggling season. During this year’s smuggling season, just 25 smuggling attempts took place, compared with 65 attempts during the last smuggling season.

The effects on local communities—even within the first several months of this new status quo—have been significant. With carriers and transporters cut off from their smuggling groups, border communities are increasingly home to newly unemployed armed men who previously made money from the trade. Moreover, the abrupt collapse of the Assad regime led to wide-scale looting of regime positions across south Syria that has flooded the local market with weapons and other military materiel. During multiple interviews local community leaders shared similar concerns: that despite an overall decrease in smuggling, the root causes for future instability and criminal activity remain without any future prospects for long-term economic recovery across all of Syria. As Syria navigates a fragile transitional period and struggles to create a unified army capable of securing the country’s borders and offer an economic path forward, the current smuggling downturn should not be seen as permanent. There remains a very real possibility that further security and economic fragmentation in the country may lead to a resurgence in cross-border trafficking of drugs and weapons.

Recent Changes to Smuggling Networks in South Syria

The collapse of the Assad regime on 8th December 2024 ostensibly ended the regime and Hezbollah’s direct support of drug smuggling in south Syria. The loss of this high-level organization has ended the industrial-scale narcotics operation run by the regime and seriously hindered—although not ended—cross-border drug smuggling operations by criminal groups in south Syria. In the immediate aftermath of the collapse of the Assad regime, ETANA assessed that cross-border smuggling had slowed but not halted altogether. In total, 25 attempts were monitored between 8th December and mid-January, compared with 65 attempts during the same period in 2023-2024.

As a result, ETANA estimates the total number of smugglers in Suwayda province decreased by nearly 40%. At least 19 groups disbanded entirely, while virtually every smuggling group decreased in size. Most of the groups that remain are the remnants of the most prominent and effective smuggling groups, whereas the smaller and less entrenched groups have mostly dispersed. The smugglers who remain face serious challenges: the new Syrian caretaker authorities as well as local authorities in south Syria have taken measures to curtail illicit activities, seizing drug production and storage facilities and cutting off supply routes. The major local players in south Syria’s drug trade have also begun downsizing their operations, adopting a wait-and-see approach for the time being.

Ongoing Smuggling Operations

Following the collapse of the regime, the smuggling groups that are still active are focused on transporting small quantities of illicit goods across the border without support and supplies from kingpin drug dealers with direct connections to the Assad regime and Hezbollah. Previously, drug smugglers moved product that belonged to traders and suppliers and were given a cut of profits following successful operations. These outside entities wielded enormous influence over smugglers, dictating when an operation would take place and how much product needed to be moved at a given border crossing.

Today, local drug smuggling groups are responsible for the details of their own operations, including procurement and purchase of illicit material, transport, labor, tactics and crossings, whereas under the regime’s systematic operations there was a division of labor and specializations assigned to different groups across various stages of the smuggling operation. Operations are now much smaller than in previous years, transporting significantly lower quantities. Currently, the most effective means for transporting drugs across the Syrian-Jordanian border is to utilize drones, which are now easily available on the local market.

South Syria as the End-Market

Smuggling along the Syrian-Jordanian border is not a new phenomenon, but rather an activity that traces back decades. The notable change during the Syrian conflict was the state-sanctioned industrialization of existing infrastructure that flooded neighboring countries with drugs and weapons worth billions of dollars under the auspices of the Assad regime and Hezbollah to support the operations of both. Since the collapse of the regime and the localization of smuggling operations by groups in south Syria, the domestic market—which is far less lucrative—is currently the main outlet for drugs and weapons trafficking.

South Syria’s New Drug Market

The abrupt disruption of cross-border drug smuggling led to major changes in the local market in south Syria. Most drugs that entered south Syria prior to the fall of the regime simply transited the area before being smuggled to Jordan and the Arab Gulf, where it is much more profitable to sell drugs than in economically disadvantaged Syria. With almost no new domestic Captagon production and disruptions in the supply lines for hashish from Lebanon and crystal meth from Iraq, smuggling groups in the south have primarily sought to offload existing supplies into the local market. With a currently reduced supply, the result is higher prices for local drug users despite a general drop in quality for most types of narcotics, reaching as much as double the pre-December 2024 prices for hash, Captagon and crystal meth. These increased prices are most likely the result of unstable supply chains and a fear from drug dealers that they will be unable to procure more drugs when current stockpiles run out.

Proliferation of Weapons in South Syria

One of the most notable trends in the months following the collapse of the regime has been a massive influx of weapons into the local black market. As regime forces abandoned their positions throughout the south, local fighters and criminal elements looted outposts and bases belonging to the former regime and seized large quantities of weapons, ammunition and military-grade equipment. The abundance of former regime weapons on the local black market has not translated into increased cross-border smuggling, however. As with drugs, the rate of weapons smuggling across the Syrian-Jordanian border has decreased dramatically following the collapse of the regime and the departure of Hezbollah and Iran from the area. From 2018 until 2024, the regime cooperated with Hezbollah to smuggle weapons across the border to supply its regional proxies with weapons. For the time being, Iran’s geopolitical goals have been constrained, and groups smuggle weapons solely to generate profit.

The proliferation of weapons throughout the south—particularly amid tensions with the new government in Damascus and the lack of central authority—raises serious concerns about safety for local Syrians. An additional concern comes from the sheer number of freelance fighters in the south: now out-of-work smugglers still face the same economic pressures that drove them towards criminal activity in the first place, but they are currently unable to make money from illicit smuggling. The combination of freelance fighters, worsening economic conditions and an unprecedented abundance of weapons remains concerning.

Survey Findings on Post-Assad Smuggling Networks & their Effect on Border Communities

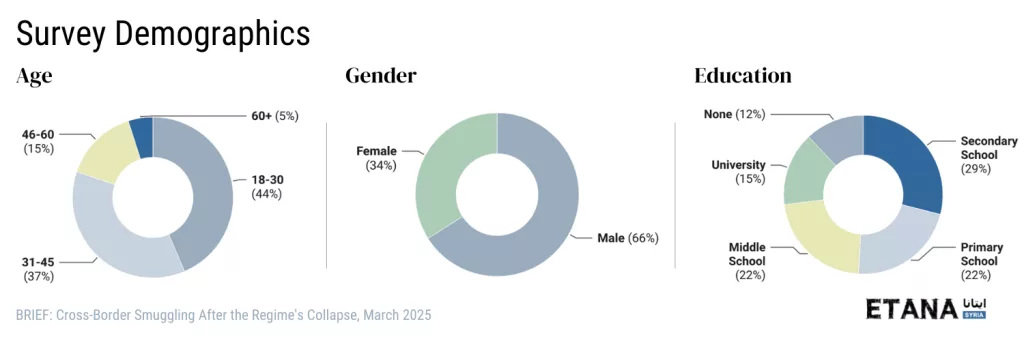

Following the collapse of the Assad regime in December 2024 in Syria, ETANA sought to better understand the views and experiences of Syrians regarding cross-border smuggling. To do so, ETANA conducted a survey of community perceptions regarding smuggling dynamics in February 2025, a few months after the Assad regime’s collapse across the province of Suwayda. The province shares a vast border area with Jordan and that has been the site of most smuggling activity of drugs and arms from Syria into Jordan in recent years.

A total of 41 individuals from across Suwayda province, including border towns and villages, were interviewed for this survey.

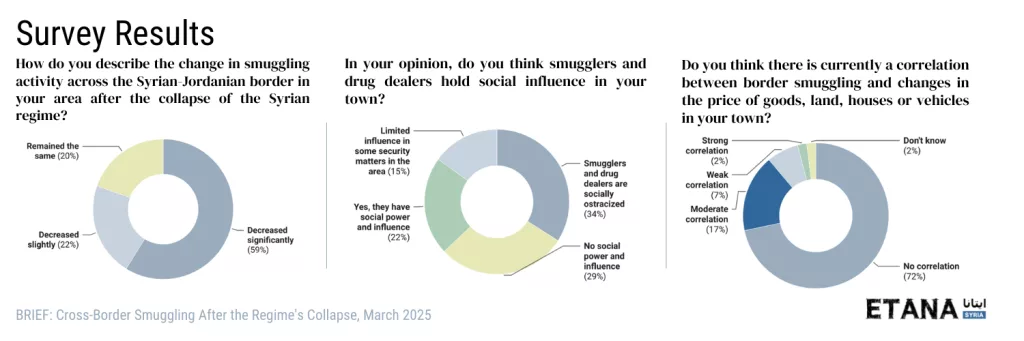

Following the collapse of the Syrian regime, most respondents in Syria reported perceiving a decrease in cross-border smuggling activity in their area, although a higher level of respondents reported some level of decrease at 81%, while 59% stated it had decreased significantly. Respondents suggested several reasons for the decrease in smuggling from Syria to Jordan, and the lack of security cover and facilitation from the regime for smugglers was cited as arguably the most significant reason. However, several additional important factors included fear of Jordan’s counter-narcotics response including ground operations into Syrian territory or airstrikes; border patrols by local armed groups in Suwayda working to prevent smuggling; and the lack of conducive weather conditions this winter season.

When asked whether drug smugglers hold social influence in their communities, the overall sentiment leaned against drug dealers and smugglers having social influence in their communities, with 34% stating that they were ostracized, 29% reporting that they did not have social power and influence, while 15% said they had limited influence over some security matters in the area. Only 22% stated that they wielded social power and influence in their communities.

South Syria is one of the most economically disadvantaged areas in a country where 90% of the population is already estimated to live below the poverty line. For many, smuggling is a means to enrich oneself and one’s family amid the extremely poor economic conditions in the region. For others, the influx of drugs and weapons into economically disadvantaged communities has been devastating for some of the area’s most vulnerable populations. The south has faced severe destruction, front-line fighting, deprivation of financial resources and services and punitive measures at the hands of the former regime. In the weeks following the regime’s collapse, the economic situation continued to worsen across country and in the south, and there are few signs that indicate that the situation will improve in the immediate future.