Hundreds of thousands of Syrian returnees have entered regime-held Syria since late September—many for the first time in years—but relatively little is known about returnees’ prospects after return.

Throughout October, ETANA conducted a 57-person survey with returning populations to gather qualitative data on returnee demographics, push and pull factors, experiences at official or unofficial border crossings, and experiences during displacement and return. Most survey participants were, until recently, living in Dahiyeh, south Lebanon or the Beqaa Valley—areas often associated with Hezbollah that have witnessed heavy Israeli aerial attacks and/or ground incursions since September. Most returns were therefore motivated by violence in Lebanon and not conditions in Syria. Current refugee movements into Syria do not change the fact that Syria is not a safe returns context.

ETANA now estimates that at least 130 people have already been arbitrarily arrested at official border crossings or checkpoints inside Syria either because they were wanted for security reasons or military service. The latest indications suggest that regime security agencies are focusing their attentions on returnees after they arrive at their intended destination. From an optics perspective, this is a preferrable option for the regime: arrests at official border crossings risk being documented by UNHCR representatives present at crossings; but without an independent post-returns monitoring mechanism inside Syria, arrests can take place with less risk of information getting out. As such, observers should expect to see notable upticks in detentions in return locations in the coming period.

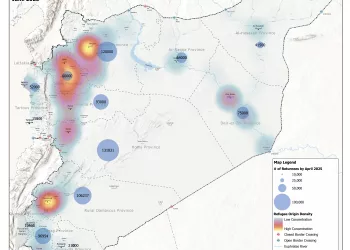

The high rates of returnees entering Syria has shifted in recent weeks. As of mid-October, an estimated 35,000 refugees originally from Daraa have fled from Lebanon to Syria, but returnee movements slowed in the second half of the month. Additionally, a small trickle of Syrian migrant workers—their numbers estimated at 2,400 people—have begun to return to Lebanon, many under threat of having their work contracts cancelled by their Lebanese employers.

Background: Recent Displacements from Lebanon to Syria

Cross-border clashes between Hezbollah and Israel became semi-regular occurrences following the Hamas incursion into southern Israel in October 2023. The front shifted, however, when Israel’s security cabinet announced on 17th September its intention to refocus fighting away from Gaza—supposedly with the aim of “returning the residents of the north securely to their homes”—and to escalate conflict with Hezbollah.

After two days of attacks using weaponized pagers and walkie-talkies to target Hezbollah fighters and civilians, Israel significantly escalated airstrikes against Hezbollah targets and civilian areas from 23rd September before launching a ground invasion in early October. Much of Hezbollah’s top leadership structures have been decimated—culminating in the shock assassination of Hassan Nasrallah on 27th September—while Hezbollah fighters in south Lebanon are now locked into dogged guerilla fighting against advancing Israeli troops.

The Lebanon front has been devastating to civilian populations, and most recent estimates hold that already more than 800,000 people have been internally displaced within Lebanon—many of them Syrian refugees displaced by the war in their home country. Reporting by UNHCR and the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC) estimates that 425,000 people—72% of them Syrians—crossed into Syria since the escalation in Lebanon over a month ago. Syria’s Immigration and Passports Department, which is present at official border crossings, has meanwhile documented 315,000 people—including 105,000 Lebanese refugees and 210,000 Syrian returnees—arriving to Syria through official crossings during the same period. The true number is in fact likely much higher: because of changing entry regulations and fears of abuse at the hands of the regime’s security agencies, many Syrians are opting to travel through unofficial crossings and enter the country irregularly and undetected.

The latest displacements represent, in the words of UNHCR chief Fillipo Grandi, a “terrible, sad tragic irony.” Syria, a country still in its own state of unpredictable, protracted conflict, has seen around half of its entire population displaced inside and outside the country since 2011. Now, it is absorbing hundreds of thousands of refugees from Lebanon as well. Even so, this should not be understood as evidence that return conditions in Syria have changed. While some countries are closely watching the flow of Syrians from Lebanon back to Syria and re-considering their assessments of protection risks in Syria, current refugee movements do not change the fact that Syria is categorically not a safe returns context. Beyond the chaotic, unsafe journeys undertaken by returnees, the following study demonstrates that the regime is continuing to arbitrarily detain, conscript and forcibly disappear returnees who are picked out of queues at the border or at checkpoints and transport hubs along their routes through regime-held areas of Syria. Those arriving via smuggling routes are also not safe: the regime has an extensive range of repressive and prosecutorial tools at its disposal to process returnees and pursue perceived dissidents, or anyone with links to them, long after they return.

Survey Findings

Throughout October 2024, ETANA conducted 57 interviews with Syrian returnees who were either in the process of returning to Syria or who had already reached their intended destination in regime-held areas or opposition-held areas of the north-west. Surveys were based on a structured survey questionnaire that sought to gather qualitative data on returnee demographics, push and pull factors, experiences at official or unofficial border crossings, and experiences during displacement and return.

ETANA interviewed 57 Syrian returnees during the survey process, more than half (60%) of whom were between the ages of 18 and 35 years’ old. Some 69% were men and 29% women. Nearly 40% of respondents had been living in Lebanon for a decade or more, part of historic displacements from the first few years of the Syrian uprising and ensuing conflict.

The difficulty of creating a genuinely representative survey sample among people on the move or recently arrived in a new location led to one or two differences in the survey sample compared with reporting by media and aid organizations. While ETANA found it difficult to practically and sensitively reach female respondents during the course of their displacement, UNHCR has stated that the majority of recent Syrian returnees are women and children. In late September, for example, UNHCR estimated that 60% of Syrian returnees were children, with many male relatives opting to stay behind in Lebanon, leaving families separated. Additionally, ETANA’s survey sample recorded 12% of respondents who entered Syria informally, whereas the proportion of informal vs. formal crossings is believed to be significantly higher because military-age males and wanted persons aim to reduce or avoid interactions with regime authorities during return.

Displacement Logistics

There are several steps involved in moving through an official crossing:

- After leaving the Lebanese side of the border, returnees are first received by a Syrian checkpoint that takes a bribe of between 5,000 and 10,000 SYP (around $0.38 and $0.76, respectively) for each elderly, female or juvenile returnee. This is an ordinary part of the crossing process under the pretext of facilitating a traveler’s affairs and “speeding up” their entry.

- Returnees then proceed to the Immigration and Passports Department to stamp their passport and, if their exit from Syria is considered illegal in line with Law 18/2014, settle their status. This also involves a bribe: this time, between 20,000 and 50,000 SYP (around $1.54 and $3.84 respectively) per person.

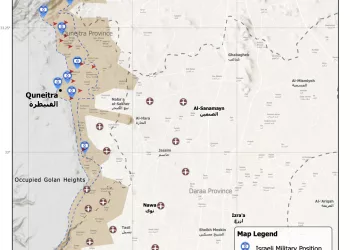

- If there are wanted persons found among returnees, they are separated at this point and gathered on a bus operated by governorate-level police forces. From there, they are taken to the required security branch before the end of the same day. If there are individuals wanted for mandatory military service among returnees, they are then required them to present themselves at the local recruitment department within 15 days of entering Syria. A higher bribe, of up to 200,000 SYP (approximately $15) is also required for draft dodgers at this point; this is required to cross and does not absolve the payer from military service or prevent them from receiving a summons.

- Afterwards, remaining returnees proceed through customs, where their belongings are searched.

- They are then allowed to proceed to tents operated by the Syrian Arab Red Crescent (SARC). Here, SARC provides medical services and transfers anyone in need of hospital treatment to a nearby facility. If returnees are from far-off areas of the country such as Aleppo, Deir Ezzor or Raqqa, they have the option to board expensive private buses at their own expense—one survey participant recounted paying up to 400,000 SYP (nearly $31) for one ticket to rural Aleppo via Hama.

Young men—including those wanted for military service or for evading military service in the past—are more likely to cross through unofficial crossings to completely avoid or limit interactions with Syrian authorities. While some individuals at official crossings are offered a route by smugglers that takes them from the “no-man’s land” between Lebanese and Syrian border posts, most unofficial crossings take place in remote, mountainous areas such as northern Lebanon’s Walid Khaled region.

Onward Journeys/Displacements

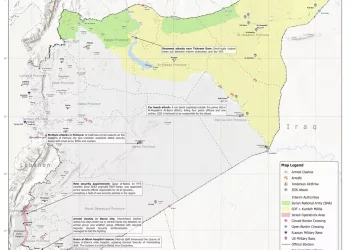

Respondents’ intended destinations were relatively mixed, with around 41% travelling to Daraa and 43% travelling to regime- or opposition-held areas of the north-west. All but two returnees knew in advance their destination, with return dynamics largely dictated by prior family connections in a return location.

Untold thousands fleeing Lebanon have taken convoluted, exorbitant routes from the border, through territory held by the regime and Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), towards the Aoun al-Dadat crossing that borders areas of the north-west held by Türkiye and the Turkish-backed Syrian National Army (SNA). For returnees attempting this journey—again, largely because they originally came from the region, or because relatives had been displaced there from other areas during the conflict—there are additional challenges. Returnees finding themselves in SDF-held areas near the Aoun al-Dadat crossing have been subject to long delays and extortion by local gangs.

Bribery & Harassment at Checkpoints

Bribes do not just happen at the border: almost all survey respondents (93%) described experiencing financial extortion during their journey from Lebanon to Syria. At official border crossings, bribes are a matter of procedure under the pretext of supposedly speed up a returnee’s progress through the border or to shield them from predatory security practices. After crossing the border, extortion is routine and procedural—implemented as understood fees that must be paid—with bribes levied by 4th Division troops and other regime security agencies at various checkpoints along the way.

Respondents estimated passing through, on average, nine checkpoints before reaching their intended destination, with most of these in regime-held areas. One respondent described being “extorted multiple times, even though we paid the full amount to the transport company, including bribes for checkpoints,” with some checkpoints asking for cigarettes, “[and] others for fixed rates.” Another said that checkpoints tended to be “smoother” for families and children compared to groups including young men.

That being said, the threats spoke to the actual risks faced by returnees. Anyone from an area associated with significant and historic opposition activity can face extra scrutiny (and harassment and abuse). One respondent, who remembered travelling with a young man from Idlib, said: “When [the checkpoint troops] found out he was from Idlib, they beat and insulted him.”

In total, a significant majority—91%—said they experienced threats at border crossings or internal checkpoints during their displacement journeys.

Detentions & Other Protection Risks

Between 4th and 10th October, ETANA was aware of tens of arrests by Syrian authorities at an official border crossing bordering Homs province and now counts approximately 130 arbitrary arrests that have taken place at official border crossings or regime checkpoints after the Syrian-Lebanese border.

Open-source reporting has uncovered other arrests away from the border. A report by Syrian outlet Al-Jumhuriya in early October also indicated that 40 people were arrested at the Pullman Garages bus station near Al-Qaboun in eastern Damascus city and in Homs after returning from Lebanon, although ETANA was unable to independently verify these reports.

Several survey respondents witnessed arrests. Nine respondents (16%) mentioned cases of arrests of individuals taken from their group (all men) or cases they heard about during their crossing (including some women detained for unknown, but likely security, reasons). Cases included military-age males who previously defected from the Syrian army being taken away at border crossings.

One female returnee’s husband, a defector, was arrested despite paying a smuggler to transport him through regime-held areas and avoid regime checkpoints: “He wasn’t with us on the same bus [because] he arranged his trip with a smuggler who assured him safe passage through regime checkpoints and promised to deliver him safely to opposition areas,” she remembered. “However, we learned that he was arrested at one of the checkpoints. To this day, we have no information about him.”

For years, observers seeking to push for refugee returns to Syria have pointed to the reduced number of arrests and enforced disappearances compared with the horrific practices earlier in the conflict to argue that Syria is in fact relatively safe. Although the proportion of detainees is small compared to the total number of returning Syrians, it is important to remember that detentions and conscriptions are part of the regime’s standard operating procedure—if someone’s name appears on a list or they are more loosely regarded as a “person of interest,” their trajectory upon return is set. The above case study also demonstrates how those with security profiles are being processed and prosecuted in almost identical ways to the height of the regime’s detention practices between 2011 and 2019.

Return risks do not stop once a returnee has crossed the border; there are several ways that the regime can seek out returnees once they settle in regime-held areas. When a new returnee applies for services or civil status documentation, their name will be flagged to security agencies if they are wanted or designated as a person of interest. Mouraja’a (review) summons are a common tactic used by security branches, whereby returnees are “invited” for supposedly informal conversations at security branches that can turn into detention situations after days, weeks or even months of repeat summons and interrogations. Localized revenge provides another ground for detention and prosecution: for years, civilians and local regime cronies have used malicious lawsuits as one way of settling old scores and ensnaring individuals, families and whole communities accused of opposition activity since 2011.