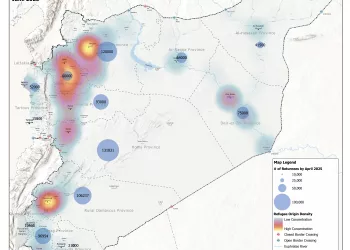

This past Friday an estimated 800-1,000 residents in Suwayda turned out to celebrate the one-year anniversary of their protest movement against the regime of Bashar al-Assad. The movement, which began in August 2023, has been sustained by near-daily protests in Suwayda city and in smaller towns across the countryside. The movement spread quickly: between 16 August and 16 October last year, ETANA recorded nearly 500 anti-regime protests in south-west Syria. More than three-quarters of these took place in Suwayda province.

Initially sparked by economic grievances, the movement quickly expanded to demand political reforms, military service exemptions, and the removal of Iran and Hezbollah from south Syria. The Suwayda protests have not only exposed the fragility of Assad’s rule but have also called to attention the growing dissatisfaction felt by historically loyalist or neutral communities.

Concerns & demands

Suwayda was unanimous in its support for socio-economic demands from the regime, including increased and improved public services, reduction of commodity prices, continued military service exemptions and the release of detainees. There was, however, disagreement on the extent to which they wanted to demand political changes from the regime—and whether to outright demand Assad’s removal from power. Their demands also include the implementation of UN Resolution 2254.

On 26th August, local protesters established a consultative committee to better centralize the movement’s demands and organize demonstrations. Women and local women’s organizations have been heavily involved in these committees and have also been at the forefront of street protests.

Regime reactions

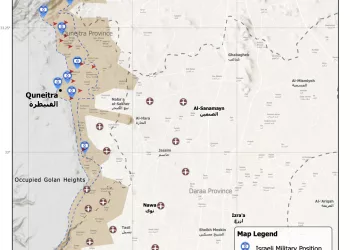

So far, Suwayda has avoided a large-scale regime crackdown. Recognizing the complexities of the Druze community and its historic relationship with Syrian minorities, Damascus likely calculates that attacking Suwayda outright is too great a risk. Not only would a crackdown risk pulling in Druze communities from Lebanon and Israel, but doing so would also risk the regime’s relationship with other minorities that normally enjoy its nominal protection.

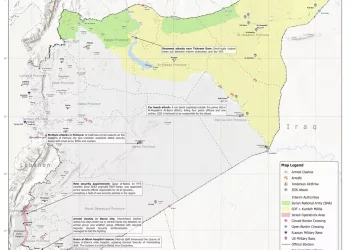

At the same time, expressions of solidarity with the traditionally insular community have been shared from Daraa and the opposition-held north-west, where residents are leading their own protest movement against Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham (HTS).

Over the course of the past year, Damascus has worked to strike the popular movement with accusations of treason and to plant regime-backed security groups to threaten, divide and destabilize the movement. This has not dissuaded the population from their demands, even if the size and frequency of protests has gradually declined since the beginning of 2024.

Background

In mid-2018, Syrian regime forces defeated the armed opposition in the south, but the subsequent Russia-mediated patchwork of reconciliation deals failed to ensure the return of governance and stability. Today, the south is regime-held in name only: local armed groups compete or coordinate with Iranian-backed militias and regime security services vie for influence and profits through the immensely lucrative illicit drugs trade. Civilians are caught in the middle of the violence, wherein armed groups frequently clash in a tit-for-tat cycle of retaliations.

For the most part, Suwayda’s unique identity protected it. Like his father before him, Assad gave concessions to Syria’s minorities in return for their loyalty. This dynamic benefited the regime in 2011, when Suwayda’s Druze community was divided among those wanting to remain neutral (the majority), those wanting to support the regime against the opposition, and those in favor of the nationwide opposition movement. The regime has in the past employed targeted violence against opposition figures in Suwayda looking to link up the province’s demands with opposition movements elsewhere in the country—including the destabilizing 2015 killing of Men of Dignity Movement leader Wahid al-Balous or the more recent killing of opposition commander Merhej al-Jaramani earlier this year—contributing to persistent fears about what bodes next for Suwayda.